Originally published in New Socialist, January 6, 2022

The history of coal mining in Britain, focusing on the South Wales and Durham coalfields, their insertion into imperialism, the gendered regimes of production, and class struggle.

17664 words / 69 min read

At the beginning of July 2021, Chancellor Rishi Sunak decided the government would keep billions of pounds generated by the miners’ pension scheme (1), ignoring a recommendation from the Commons Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee to return the money to the scheme and so fund a £14 weekly pension increase for 124,000 ex-miners. This perfectly captures the toxic embrace in which the British state has held mineworkers, and the subordination of the interests of miners to a “national” interest, determined broadly by the interests of capital (though impacted by the class struggle of the miners), for over a century and is one of the themes of Huw Beynon and Ray Hudson’s superb and timely new book The Shadow of the Mine: Coal and the End of Industrial Britain. During both the rise and decline of coalmining, the British state was closely involved in ensuring its strategic economic interests were safeguarded under first private ownership then public ownership then private ownership again, while also attempting to counter the potential and actual power of the mineworkers union. The state at various points subsidised coalmining, took the industry under temporary state direction and regularly backed the private coal owners in disputes with mineworkers. Reluctant to bring coalmining into public ownership, the state supported the private mine owners, despite their inefficiency and mismanagement, until the position became untenable and the interests of capital left little option but to nationalise the industry. So, in 1947 the state became the direct employer with all the potential for conflict that entailed over jobs, pay, conditions, pensions and much more.

This book is many things. Beynon and Hudson set themselves the task of answering the question ”Whatever happened to the miners?”. In doing so, the book is at once a panoramic review of the rise and decline of the UK coal industry and its central place in the development of British capitalism; a history of the coalfield communities of South Wales and Durham; an examination of the social place of mineworkers’ unions – the South Wales Miners Federation (later the South Wales Area NUM) and the Durham Miners Association – and their pivotal role in the labour movement in both these areas. As the “deep story of a disenfranchised working class” (p.2) it also helps to explain “the anger that exploded into the 2016 referendum and the 2019 general election” (p.6).

Referencing Michael Burawoy, the authors outline what they describe as “a coal mining regime of production” (p.14) based on a rigid division of labour between men’s labour at the pit and women’s labour in the home, supporting production in the mine. Beynon and Hudson contrast the development of the coal mining regime of production in South Wales and Durham with the way that mining developed in some other areas of the world. In many places mine owners created dormitory facilities to house and feed their workers, whereas in South Wales and Durham, these tasks fell to the women at home in the pit villages – caring for the miners and their children, preparing hot baths and meals, the never-ending job of washing clothes. Often all the men of a family would be employed in the pit, sometimes on different shifts, so the women would “cater for the needs of the husband and sons as they left for work on different shifts, to return at different times tired, dirty and hungry” (p.14) – mining families’ routines “were geared to the rhythms of the mine” (p.14).

The 1842 Mines and Collieries Act made it illegal for women to work underground, but their (unpaid) domestic labour remained of critical importance for coalmining. It was unrecognised but essential to the functioning of the industry and both marked women’s labour as ‘unproductive’ and elevated the power of men in the family and community. There were few employment options for women in pit villages but that did not mean that they engaged only in domestic labour. The authors explain that they played an important part in community life in the chapels and co-ops and were active in protests and strikes, organising food provision, supporting strikers and shaming scabs. Far from a novel development in 1984-85, the activity of Women Against Pit Closures was part of a long tradition in the coalfields.

The book explains how two — essentially countryside — regions of the UK became highly industrialised and then a century and a half later became de-industrialised without reverting to rurality. Based on decades of research by the authors, this book is full of lessons and insights for today – on the composition, decomposition and potential recomposition of the working class; on the capacity of working people to build powerful institutions of their own in their communities centred around their trade union; on the failures of capitalism and the state to rebuild and restructure in the wake of economic change; on the political impact for the British Labour party of “the sense of betrayal of communities” (p.5) in terms of understanding the Brexit vote and the fall of the so-called Red Wall; and of the possible sources of hope for radical renewal in coalfield communities and beyond.

In the coalfields, there was, in Edward Thompson’s words, the “making” of a working class which, through its agency, was “present at its own making”(2). The politicisation of miners and their communities led to the building of support for, and feeling of ownership of, Labour as their party. So first the authors show how largely rural areas became dramatically transformed – economically, socially, politically – as the discovery and exploitation of coal thrust them into the vanguard of industrialisation. In their words: “No coal, no industrial revolution in Britain” (p.2).

And although the authors do not use the term ‘imperialism’, they describe the close relationship between coalmining, British military power through the Royal Navy and economic power through the export of coal (p.2). On Barak argues that “Britain’s industrialization and imperialism were not separate processes: both – not only the former – were predicated on coal.”(3) But the presence of large deposits of coal was not enough in itself to drive industrialisation. Jason W. Moore argues that the expansion of the British cotton industry (which became the major customer for coal as a source of power) was only possible because of “the reinvention of slavery – across the Americas but especially in the American South”. Slavery drove down the cost of cotton and together with other factors associated with imperialism such as the dispossession of Indigenous people and appropriation of a robust strain of cotton which they had developed, laid the basis for the advent of large-scale factory production in Britain. There was a further more direct link with slavery and the slave trade in that much of the capital for the development of mining (and iron production) came from the plantocracy and slave traders. Eric Williams famously (and controversially) argued in his 1944 work, Capitalism and Slavery that the profits from the triangular trade were a major, if not decisive, factor in the capital accumulation required for British industrialisation(4). At the very least, as Robin Blackburn explains(5), there was an important inter-relationship and a stimulus. Peter Fryer collates a wide range of sources to show that “capital for South Wales industry was obtained in the eighteenth century partly from Bristol and London merchants, much of whose wealth had originally been derived from the slave trade”(6). One of the differences with South Wales was that the Durham coalfield, by contrast, was developed by the landowning aristocracy that transformed itself into a capitalist class.

The authors explore the differences between the two coalfields – in their geology, their geography, the contrasts between the history, structure and politics of the miners’ unions in each area – as well as the similarities, in that they were “both regions at the centre of a single fuel industrial economy” (p.7), both areas with high quality export coal in which miners’ organisation became of critical importance in local life.

Before the General Strike

New communities were built, old ones were reconfigured as collieries were sunk throughout the coalfields of South Wales and Durham. People surged into these areas to work the black gold. In South Wales, they came from the Welsh farming districts, from the West Country (the great miners’ leader A. J. Cook was from Somerset for instance) and the Midlands of England, from Ireland and further afield, for example, a significant group of Spanish miners arrived, bringing with them anarchist and socialist ideas. There was even a branch of PSOE, the Spanish Socialist Workers Party in Dowlais in 1903(7). By 1911 two thirds of the Welsh population were concentrated in the two mining counties of Glamorganshire and Monmouthshire. In 1913 the South Wales coalfield employed 230,000 men(8) and by 1921, one third of Wales’ entire male labour force worked in the mines and quarries (p.19).

The rapid expansion of coalmining – particularly in South Wales – coincided with a crisis in European agriculture, detonated by new American competition which hit hard in the 1880s. The collapse of rural economies across Europe fuelled mass migration to North America from Ireland, Germany, Italy and Scandinavia. In Britain and Ireland, when the export sector boomed, people from rural areas emigrated, when the home sector was in the ascendancy, displaced rural populations could be absorbed in the home economy. Throughout Britain and Ireland, this pattern of migration or absorption took place – except in Wales. G. A. Williams explains this by describing the formation of the industrial society of nineteenth century Wales as being “peculiarly imperial”(9), with its export-centred economy (essentially that of the South Wales coalfield) expanding most when British industry as a whole expanded least. Coal then was essential to the “national interest” not only for powering industry in Britain but for export earnings. Coal could be exported relatively cheaply because ships carrying bulk raw materials imports into Britain could be reloaded with high value but small bulk exports together with export coal (when otherwise the ships would have had to leave Britain half empty or in ballast)(10). Before World War One, Britain controlled 70% of the global sea trade in coal and up to World War Two, the most important internationally traded form of energy was British coal(11), and most of that exported coal came from South Wales and Durham. Smith describes South Wales as having an ‘Atlantic’ rhythm of growth compared to the rest of the British economy:

For over two decades, more than one-third of all exported British coal came from a south Wales whose coalfield was a major supplier of industrializing France and Italy, of colonial Egypt, of developing Brazil and Argentina. In its south-west section 90 per cent of all British anthracite was mined, with over 55 per cent shipped out, mostly to new markets in Scandinavia and France(12).

Until the 1860s Wales lost substantial numbers to emigration but in the 1880s rural Wales lost 100,000 people but few emigrated, in contrast to other parts of Britain facing similar problems. Many displaced from rural agricultural Wales were absorbed into the expanding industrial South Wales. Just as British emigration hits a peak, emigration from Wales becomes negligible as there is a dramatic increase in the absorptive capacity of the South Wales coalfield. In fact, Wales becomes a place of net immigration, second only to the USA in the decade before the First World War in terms of immigration rates. These new communities based around the pit became part of the gendered “coal mining regime of production”, perhaps in much the same way as Moore’s observation of the enclosures in England after 1760 as “profoundly gendered, disproportionately proletarianising women, and yielding a kind of ‘gendered surplus’ to capital in the form of lower remuneration relative to men.”(13)

Miners built their industrial strength through their organisations and needed it during the Great Unrest between 1910 and the beginning of the First World War in which the tempo of class conflict rose right across Britain. The South Wales coalfield was a particular flashpoint where, according to The Times, “in no other coalfield is there such strife and distrust of the owners”(14). The Cambrian Combine dispute led to the Tonypandy riots and the deployment of the Metropolitan Police and the mobilisation of the army against the perceived threat to ‘order’. The growth in support for revolutionary syndicalist thinking among miner activists across the coalfield was reflected in the work of a group of South Wales miners who wrote “The Miners’ Next Step” in 1912, calling for the reorganisation of the South Wales Miners Federation (‘the Fed’) into:

A united industrial organisation, which, recognising the war of interest between workers and employers, is constructed on fighting lines, allowing for a rapid and simultaneous stoppage of wheels throughout the mining industry.

The outbreak of war curtailed, but didn’t eliminate, unrest in the coalfields and after Lloyd George returned the pits to the coal owners after the war (having brought the industry under government control for the duration of hostilities) in 1921 the owners then demanded a 50% wage cut from the miners. When the miners refused, the owners locked out a million workers. In what became known as ‘Black Friday’, the Triple Alliance of miners, rail and transport workers collapsed and the miners were defeated. But neither the economic problems of the industry nor the determination of the miners to achieve a decent life disappeared. Radicalism continued to grow in South Wales, to the extent that the Fed voted to affiliate to the Red International of Labour Unions, the trade union arm of the newly formed Communist International(15).

The General Strike

By 1925 the coal owners demanded a further cut in pay and increase in hours. The response of the miners was so solid that the government stepped in with a subsidy for wage levels for nine months. A. J. Cook, formerly the leader of the Fed, but by now leader of the Miners Federation of Great Britain (MFGB), was elated at this decision, which became known as ‘Red Friday’ but he warned that it was just an armistice, not a victory. Beynon and Hudson note that one of the Durham coal owners, Lord Londonderry, was brutally frank about what was coming the miners’ way and in words that could have come from Thatcher decades later, declared: “Whatever it may cost in blood and treasure, we shall find that the trade unions will be smashed from top to bottom.” (p.22)

And so it proved to be. When the subsidy ended and the owners demanded cuts in pay, increased hours and an end to national agreements, the miners struck. Having forced concessions from the government and employers in 1925, the miners expected the support of the wider trade union movement to be the critical factor in winning what was, after all, a defensive dispute. Having failed the miners on Black Friday in 1921, there was undoubtedly great sympathy for the miners among the working class as a whole and the conference of union executives was unanimous in supporting the proposal for strike action. A General Strike was called in their support and for nine days millions of workers led by the TUC General Council and its affiliated unions struck in waves of solidarity with the miners.

However, there were already warning signs of danger for the miners. The TUC did virtually no planning until the week before the strike, presumably because they hoped for and expected a settlement. They thought the threat of a strike on this scale would be enough to force a retreat on both the employers and the government. They misjudged the attitudes of both. The coal owners were determined to boost profits at the expense of the miners, after the damaging impact on exports of the return to the gold standard in 1925. Meanwhile the government had begun preparations (of which the TUC were unaware) to defeat the expected strike immediately after Red Friday in July 1925.

In the view of the TUC leaders, if the strike went ahead at all, it would simply be a sympathy strike on a grand scale. Unusual but still an industrial dispute. They did not reckon on the government interpreting it as a political strike from the beginning (which of course it was) and an organised attack on capitalism (which it was not). The government mouthpiece, The British Gazette, declared that this was “not a dispute between employers and workmen. It is a conflict between trade union leaders and parliament.”(16) While it was not a conscious assault on capitalism, a general strike by its nature poses questions of power – whether or not its leaders recognise this. The possibility that it could bring down the government was something that ministers were acutely aware of and if the government had fallen, this would have significantly changed the balance of forces between the working class and the ruling class. There were some on the union side who recognised it as a political strike and resolutely opposed it for that very reason, not least because they saw it as something that could develop in a much more radical direction. J. H. Thomas, the railway workers leader and Labour MP said in the Commons on 13th May:

What I dreaded about this strike more than anything else was this: if by any chance it should have got out of the hands of those who would be able to exercise some control, every sane man knows what would have happened(17).

Thomas was convinced that some of the General Council would be shot:

The Government will arrest the remainder and say that it is a case of putting them away for their own safety. Of course, the shooting won’t be done direct, it will be done by those damned Fascists and those fellows. You see they have come to the conclusion that they must fight…(18)

There was no clear strategy on the union side. Vic Feather (later a TUC general secretary, but a young shop steward at the time) recalls: “defence is very important, but without any ultimate objective but to defend, defend, defend, it was inevitable it should be called off. But I didn’t think that at the time.”(19) Walter Citrine, TUC acting general secretary, noted in his diary that, “we are constantly reiterating our determination not to allow the strike to be directed into an attack on the constitution” and complained that “while there is any suspicion of this it seems impossible for the government to capitulate”. He then blithely remarked that “Probably the usual British compromise will be arranged at the finish…”(20)

As the strike developed rapidly, some activists accepted the political nature of the strike but saw limited political goals. Jim Griffiths, a South Wales miner who became social security minister in Atlee’s government said: “I thought the General Strike would last a long time. I thought quite frankly that it would end in a general election; that it would become political.”(21) The young Communist Party of Great Britain also shifted its approach during the course of the nine days, adding to the defensive positioning of support for the miners’ slogan of “Not a penny off the pay, not a minute on the day” with calls for nationalisation under workers’ control and for a Labour government(22). But there was no call for a revolution or anything approaching it. The assessment of J. T. Murphy, then head of the CPGB’s Industrial Department was that the labour movement “was totally incapable of measuring up to the revolutionary implications of the situation”(23).

The British party saw itself as the British wing of the Communist International and so was deeply involved in its internal debates (which were heavily influenced by the Soviet party for obvious reasons) and rejected Trotsky’s warnings of a failure to critique the shapelessness and organisational incapacity of the Left union leaders(24). In Trotsky’s view this was tied in with the Soviet foreign policy objective of neutralising the hostility of the British state to the USSR through the creation of an Anglo-Russian Trade Union Committee (on which many of the TUC Left leaders sat). He saw this resulting in the CPGB helping to sow illusions in the Left (summed up in their slogan “All Power to the General Council”) which disarmed many activists who were consequently shocked when the Left on the General Council went along with the Right in its decisions.

Having identified the Right-wing union leaders as people who would run for cover at the merest hint of a revolutionary perspective, Murphy was far more generous to the Left union leaders on the General Council. He said:

Those who do not look for a path along which to retreat are good trade union leaders, who have sufficient character to stand firm on the demands of the miners, but they are totally incapable of moving forward to face all the implications of a united working class challenge to the state…(25)

Murphy and his comrades seemed unable to follow through the logic of this analysis. It was not that the Left leaders were consciously preparing a sell-out but that their political positions pushed them inexorably towards compromise and, in a situation where compromise was unavailable, to surrender. Bevan put it very well when he said that “the trade union leaders were theoretically unprepared for the implications involved. They had forged a revolutionary weapon without having a revolutionary intention.”(26)

Despite the numbers on strike increasing as the strike went on, the TUC leaders (both Right and Left) retreated and unanimously agreed to call off the strike without consulting the miners or securing any agreements about either the lockout or victimisation. Thomas explained very clearly why: “If it came to a fight between the strike and the constitution, heaven help us unless the government won.”(27) In other words, the implications of ‘who rules Britain’ of a successful general strike frightened them more than anything else. Cries of betrayal were certainly justified in the case of the cap-doffing, social climbing monarchist Thomas. He worked hard to prevent a strike in the first place, leaving the House of Commons “in tears on 3 May when he knew he had failed.”(28) During the strike he did his best to bring it to a close as quickly as possible, “using whatever lies and misrepresentations came ready to hand.”(29)

As for the others, Julian Symons argues that the “strike leaders numbered among themselves mules and fools, but only one traitor” (Thomas)(30). But unions have a paradoxical role in capitalist society, created as class-based organisations and reflecting the conflict of class society, they also have bureaucracies that exist to bargain with employers and as institutions arguably have a vested interest in the continued existence of this status quo. Unions may well be “unexcelled” as “schools of war” as Engels(31) put it but the bureaucracies are also “managers of discontent” in C Wright Mills’s phrase(32). Bonar Law, Conservative Prime Minister in an earlier period of sharp industrial unrest in 1919-20, noted that “the trade union organisation was the only thing between us and anarchy, and if the trade union organisation was against us the position would be hopeless.”(33) As Tony Lane observes, “trade unionism could amount to a considerable weapon of social control.”(34)

The surprise and shock on the workers’ side was echoed on the government and employers’ side (with additional relief and delight of course). Prime Minister Baldwin told the King on 13th May: “So overwhelmed were the Conservative members by the news that they found it difficult to believe that the surrender of the TUC was unconditional…”(35) while Lord Birkenhead commented that the TUC decision to call off the strike was so “humiliating that some instinctive breeding made one unwilling even to look at them.”(36)

The miners were abandoned and, although they fought on, they were starved back to work after a further seven months on strike. This was even though both South Wales and Durham voted to remain out on strike.

The failures of the TUC, the triumphalism of the owners, the lies and broken promises of the government and the memory of the hardship of the strike hung like a thick, dark cloud over the coalfields for many years spreading demoralisation and passivity and so it is not surprising that Nye Bevan observed that: “the defeat of the miners ended a phase, and from then on the pendulum swung to political action.”(37) That’s not to say there was no union fightback at all in the coalfields – there was a determined campaign to keep so-called non-political unionism out of the pits and battles over unemployment. Overall, however, the union was significantly weakened with blacklisting, aggressive management, and mass unemployment until the economic upturn on the road to another war.

Nationalisation

The miners’ union had long campaigned for the nationalisation of the mines to take the industry out of the hands of the private coal owners and after the defeat of the General Strike and the subsequent lockout in 1926, this became an ever more pressing demand of the union. The failings of the coal owners to successfully run the industry combined with its central position in the economy, and the experience of the Second World War, persuaded others of the need for state intervention. However, the form nationalisation was to take, its tendency to displace direct class contradictions in the name of a generalised working class or even “national” interest and with this the commitment of the NUM to making nationalisation work within this framework was to have baleful, probably fatal consequences.

With the election of Atlee’s post-war Labour government, it seemed that the miners’ years of campaigning and lobbying had paid off. The Nationalisation Act was passed in 1946 and the coal industry brought into public ownership from 1 January 1947 to be run by the National Coal Board (NCB) “on behalf of the people”. The coal owners received “surprisingly generous compensation terms”, which. together with the fact that they retained ownership of the profitable mining engineering and machinery sector. meant that they effectively “benefited twice from the nationalisation process” (pp.32-33). This, unsurprisingly, was strongly resented by many miners.

In the new world of nationalisation, the union was more secure, the balance of power between miners and managers had changed to a degree to the benefit of miners and some initial gains were made in pay. One of the drivers for the union’s support for state regulation of the industry was the appalling safety record of coalmining (p. 10) and, after nationalisation, the union had more influence on safety issues and safety improved(38). But essentially the same people were in charge of production, and this was to become more important as time passed.

Nevertheless, the NUM (newly constituted in 1944) – or at least its leaders of both right and left – were committed to making nationalisation work. The NUM General Secretary Arthur Horner (from South Wales) and the President Will Lawther (from Durham) worked towards this end. Horner told the 1948 conference that they needed to abandon the “class approach towards management” (p.37). In anticipation of nationalisation, Watson the Durham Area general secretary called for miners to “work all possible shifts, to cease strike action and to operate with maximum cooperation with management”. (p.33). The first director of industrial relations at the NCB was the former general secretary Ebby Edwards from Northumberland and NCB labour relations and welfare departments all over the coalfield welcomed leading trade unionists into newly created posts. On the other hand, the picture at the top was very different: Viscount Hindley formerly managing director of Powell Duffryn (one of the major private coal companies) became the first NCB chairman, and former senior managers from the old private coal companies moved seamlessly into their new positions right across the NCB.

But the government needed the support of the NUM and so some concessions were won around the Miners’ Charter at the time of nationalisation and this went alongside the uneasy incorporation of the union into the nationalised industry within a new system of negotiation and conciliation, so that ‘the Board’ and the NUM were entwined (p.34). By 1956, the situation was such that James Bowman, the former vice chairman of the MFGB and then the NUM, was appointed chairman of the NCB and “recalcitrant miners on unofficial strike were often told by their union officials that they were simply striking against themselves” (p.37). Will Paynter, president in South Wales and Sam Watson, general secretary in Durham strongly opposed unofficial action in their respective areas, Watson even going to the extent of agreeing a deal with the NCB to make miners and local lodges responsible for damages in the event of ‘unconstitutional’ strike action. Such ‘unconstitutional’ action was common in South Wales despite the disapproval of the leadership.

The miners’ leaders were acutely aware from personal experience of the harsh life imposed on coalfield communities under private ownership. They keenly felt that the sacrifices of the 1920s and 1930s followed by the war entitled miners and their communities to something more than a repetition of the relentless struggle for decent pay and working conditions against rapacious private coal owners and this had an impact on their attitude to the new nationalised industry. After years of defeat, perhaps a lowering of expectations, a willingness to compromise and an attempt to blur class contradictions is understandable. Whatever the reason, the position adopted by both Horner at UK level and Paynter in South Wales was a long way from that of their Communist Party two decades earlier during the General Strike. On 5th May 1926, its Workers’ Bulletin called for “nationalisation of the mines, without compensation for the coal-owners, under workers’ control through pit committees.”(39) In this the CP was broadly in tune with the dominant view in the MFGB in the 1920s and early 1930s, although the Labour party had adopted a technocratic, Morrisonian view of nationalisation as early as its 1929 conference(40). As the debate developed within the Labour party and the TUC in the 1930s, the MFGB focused on committing Labour to the principle of nationalisation rather than on the detail of its implementation. The union could not ignore these questions however and warned that if the miners were excluded from managerial authority “then inevitably there must grow up again all the old antagonisms between management and labour.”(41) To make their case, the miners’ leaders frequently emphasised the incompetence and inefficiency of the private coal-owners and the threat this represented to miners’ livelihoods as well as to the wider ‘national’ interest. They argued that technocratic expertise, efficiency and “some” kind of management role for miners could be accommodated within nationalisation. In TUC-Labour discussions, this came to mean “an enhanced trade union role for the MFGB, but effective power was to remain in the hands of expert, professional managers.”(42) Although there were periodic attempts within the union to revive the call for workers’ control, the leadership was concerned that the principle of nationalisation would be lost, particularly as even in the crisis of war with the demands for increased coal production, the Conservative-dominated war government had rejected nationalisation. As a result, the already ill-defined call for workers’ control became a casualty of the pragmatism of the miners’ leadership, faced with a prospective Labour government with an antipathy to what it saw as syndicalism and with a ready-made model of Morrisonian public ownership in London Transport. The MFGB grabbed this option in the belief that they could justify nationalisation through greater efficiency which would benefit both the miners and the “national” interest, but at the price of any attempt at democratic control by the workers.

Instead, what Phillips argues they got was “union voice” in having a dialogue with the National Coal Board (NCB) and government over the industry in general and pit closures in particular. He sees this as an example of what he calls (after Thompson) “the popular post-Second World War moral economy in action’ and argues that it was the threat to this ‘voice’ that was ‘the central point of contestation in the [1984-85] strike”(43). ‘Consultation’ committees rather than workers’ control became the norm and, according to some, worked well – especially in the coalfields like Nottinghamshire with its relatively accessible seams and therefore relatively high wages(44).

Coal was now meant to be an industry with a secure future, with millions of tons of accessible reserves. There would be closures of course, as coal is a finite resource, but these would be managed through a procedure agreed with the NUM based on ‘exhaustion’ of deposits (this was always a contested issue and became even more so during the 1984-85 strike around the definition of ‘uneconomic’ pits)(45). Miners would be redeployed from exhausted pits to others or government intervention would ensure that equivalent jobs would be brought into the area.

The Shift to Oil as Bourgeois Strategy in the Class Struggle

These expectations and promises of the early period of nationalisation were only very partly met. By the 1960s, UK governments, dazzled by cheap oil and the prospect of weakening the power of the NUM, seen as having a potential chokehold over the British economy, increasingly turned away from coal to oil. This was not the first time a major shift from one energy source to another was related to employers’ control over labour. Andreas Malm argues that the move from water-power to coal-fired steam was attractive because it made it easier to concentrate and discipline the workforce and offered flexibility in location (easier to bring coal to a factory than to bring a factory to the river)(46). Timothy Mitchell points out that eventually the dependence on coal and its location created a section of the working class which was heavily concentrated geographically, highly organised and had the potential to exert leverage on the mining employers in particular and on the economy in general(47). He describes this as creating a ‘carbon democracy’ in which the miners used their position to push for democratic gains. This was not unnoticed by Britain’s rulers. As First Lord of the Admiralty, Churchill saw the 1910-11 coal strikes in South Wales as a potential threat to the navy’s fuel supply and set up a Royal Commission to look at switching navy battleships from coal to oil (which in turn had an impact on British imperial policy in the Middle East)(48).

Technological advances through the introduction of power-loading machines also took their toll and government policy changed to a more market-based approach, reflecting the new competitive energy world (pp.51-52). A focus on productivity inevitably carried with it a regional bias against the more difficult to access, narrow seams of Durham and South Wales. Hundreds of closures followed under the Labour governments of the 1960s and 1970s, to the extent that discontent grew across both coalfields, although the authors trace two different leadership styles and differing responses (p.57).

After nationalisation, the political unity between Durham and South Wales established between the wars evaporated under the pressure of the Cold War. South Wales remained led by the Left, including members of the Communist party while Durham was firmly under the control of right-wing Labour Atlanticists. The Durham general secretary was the formidable and influential Sam Watson, Like Will Lawther(49) he had formerly been on the Left but moved to the Right under the pressure of the Cold War. The ability of the Right to retain control over the Durham area was at least partly to do with the more centralised power structure in Durham compared with South Wales. In the latter, the Fed as the precursor of the South Wales NUM was founded by bringing together various local independent unions and local autonomy was highly valued and written into the constitution (p. 10). The Executive was elected for a three-year term, Curtis sees the decentralised, democratic structure of the South Wales Area, which was inherited from the early years of the Fed with the influence of the syndicalist activists. as a key to explaining its radicalism.

…the democratic structure of the South Wales NUM facilitated the promotion of policies and individuals who reflected the aspirations of the broader membership. In this way, the historically created and culturally reinforced ‘traditional radicalism’ that emanated primarily from the central Valleys lodges came to play the defining role within the political culture of the Area as a whole(50).

In Durham by contrast, Executive members were elected for twelve month periods at six monthly intervals. In addition, Durham Executive members had to wait for two years before sitting on the Executive again; they were prevented from speaking on matters related to their own lodge or colliery; and lodges were not allowed to mandate delegates to the union council meetings. Whether intentional or not, this prevented continuity and experience being built up on the Durham Executive to challenge the leadership and thereby increased the power of the officials(51). In Durham the election of these officials was decided by lodge vote rather than individual ballot. Each lodge was allocated a quota of votes (maximum 6) related to membership numbers (up to 700). The larger more militant east coast lodges were disadvantaged by this. The positions of president and general secretary were not contested, all elections were for the three agents, beneath them in the structure. Successful candidates moved up the hierarchy to replace retired officials above them (p. 11). This was justified on the basis of continuity and experience (which contrasts with the reasoning for elections to the Executive).

South Wales attempted to resist the closures where possible and pressure the government to adopt “an alternative approach to the running of the industry and its relationship to energy markets” (p. 57). Durham avoided resistance but the results were broadly the same – the Wilson Labour government ploughed on with its rundown of the industry under the banner of modernisation and “the white heat of technology”. It led Will Paynter, by then NUM general secretary, to remark in a speech at a 1967 national demonstration against closures that “there was a breaking point in the tolerance and loyalty of everybody” (p.59). There was little support for the NUM from Labour MPs and little thought given to any possible threat to Labour’s electoral domination of the coalfields.

The year before, on 21 October 1966, the Merthyr Vale colliery’s waste tip slid down the side of the mountain and submerged the primary school at Aberfan, killing 147 children and teachers. In his study of working class life in Manchester in the mid nineteenth century, Engels described as “social murder” those acts in which society places “proletarians in such a position that they inevitably meet a too early and an unnatural death” and “…yet does nothing to improve these conditions.”(52) If anything qualifies as social murder, then it was the Aberfan disaster. In a section of the book entitled “Buried Alive by the NCB” (p.66), Beynon and Hudson point to this moment and contrast all its horror and grief with the widely held perception of the Board’s callous indifference (chairman Lord Robens chose to keep his engagement as Chancellor of Surrey University rather than go immediately to Aberfan). The subsequent decision of Robens on behalf of the NCB and George Thomas, on behalf of the Labour government to refuse to pay for the removal of the tip caused outrage among miners and the community, a mood which became incandescent when they found that the cost of removing the tip was to come from money raised for the disaster fund. The authors identify this complacency over Aberfan, the years of closures and their impact on communities as the beginning of the unravelling of the automatic support for Labour in the coalfields(53). Referring to pit closures, Dai Francis, South Wales Area general secretary remarked, “they dealt with the men ruthlessly. There was no difference between the old… coalowners and the National Coal Board. They were now turning it into state capitalism…”(p.68).

Between 1960 and 1980 NUM membership declined from 586,000 to 257,000 (54). There must have been more than a few historically minded NUM lodge activists who looked back at their copies of The Miners Next Step and its prescient warning in which the authors cautioned that nationalisation:

simply makes a National Trust, with all the force of the Government behind it, whose one concern will be, to see that the industry is run in such a way, as to pay the interest on the bonds, with which the coal owners are paid out, and to extract as much more profit as possible, in order to relieve the taxation of other landlords and capitalists. Our only concern is to see to it, that those who create the value receive it. And if by the force of a more perfect organisation and more militant policy, we reduce profits, we shall at the same time tend to eliminate the shareholders who own the coalfield, As they feel the increasing pressure we shall be bringing on their profits, they will loudly cry for Nationalisation. We shall and must strenuously oppose this in our own interests, and in the interests of our objective.

As the shine came off nationalisation, the coalfield communities themselves were transformed as the 1960s came to an end. Employment patterns began to change, coal mining employment declined and there was an increase in factory work and public sector employment. The latter was largely work within the welfare state and often taken up by women. And with women increasingly in paid work, and their wages being increasingly important to the family, the “coal mining regime of production” – dependent on women’s unpaid domestic labour – started to break down. There was the beginning of a fracturing of the close link between where men lived and where men worked, as miners were transferred from pits that were closing to those still working and the miners began to see themselves as “industrial gypsies” sometimes moving several times as the pace of closures increased. This may have been more significant in terms of the impact on the union in Durham than in South Wales, because of the different geological pattern in the two coalfields. In Durham the coal seams in the west of the county were relatively close to the surface, easier to mine and therefore the first to be exploited and the first to be exhausted. In the east, near the coast, the seams were deeper and extended underneath the sea (p.9). From the 1960s as closures increased and as mines were abandoned in the west, miners travelled to the east to work. Beynon and Hudson explain:

There was a noticeable build-up of miners living in the centre and west of the county travelling quite long distances to their new mine on the coast, potentially remote from the activities of the union lodge.

South Wales was different in that although closures hit jobs here too, the coal deposits lay in an oval formation across the valleys, and pits and therefore jobs were spread more evenly than in Durham with clusters of employment around a number of small towns (Abertillery, Mountain Ash, Maesteg and Ystradgynlais). So there “was no systematic spatial shift in the focus of coal production as found in Durham”. It’s hard to believe that these differing experiences did not have an impact on the class/community consciousness of the two coalfields (55).

And the politics of the coalfields were also facing new stresses and strains. That was not immediately apparent, least of all to the Labour grandees. After all, as Beynon and Hudson (p.323) point out, at the 1966 general election – just over six months before Aberfan – Labour achieved an astonishing 61% of the vote in Wales. It has never come close since (in 2019 it was 41%) and a great deal of the explanation for that can be found in the experiences of the coalfield areas in their decline. The key event in this was, obviously, the 1984-85 strike but the periods both before and after were also of critical importance.

The Crack Troops of the Working Class

The miners’ trade unions have entered into labour movement folklore as the crack troops of the working class, as the socialist vanguard. Former Tory Prime Minister Harold Macmillan famously observed, “there are three bodies that no sensible man directly challenges: the Roman Catholic Church, the Brigade of Guards and the National Union of Mineworkers.”(56)

Beynon and Hudson show that the picture was much more complex than this. The dominance of the Left within the NUM, its regions and their predecessors was neither automatic, uniform across all areas nor easily won. South Wales and Durham make good comparators in that the former quickly became a byword for militancy, under the influence of the Communist party and the Labour left (including the old Independent Labour Party), while the latter in the post nationalisation period was a bastion of the right wing under the leadership of Sam Watson(57). In fact, in the early years after World War Two, the national leaders of the NUM, TGWU and GMWU were known as the ‘praetorian guard’ because of their solid support for the right wing of the Parliamentary Labour Party(58).

But as conditions changed within the industry and within the coalfields, so did the consciousness of the miners. In 1968 the left winger Lawrence Daly was elected as general secretary, previously right wing areas like the huge Yorkshire coalfield shifted to the left, reflected in the emergence of the Barnsley Miners Forum, there was a new militancy in formerly ‘moderate’ Durham, and an ‘unofficial movement’ in South Wales. The growing mood of radicalism in response to the discontent in the coalfields saw a rash of unofficial strikes and with the election of the Conservatives in 1970 the scene was set for two national strikes. The 1972 miners’ strike was the first national strike since 1926. It was over wages and through a network of local miners’ committees, the NUM ran a highly effective, efficiently organised campaign using flying pickets, mass pickets and targeted interventions to stop the movement of coal while ensuring supplies to schools, hospitals and other socially necessary locations (p.75).

The turning point in the dispute was at Saltley Gate, a coke depot in the West Midlands, where a stockpile of almost a million tonnes of coke was ready to be used to break the miners’ strike. The NUM called for a mass picket and Arthur Scargill, leading the Yorkshire pickets, urged support from local engineering unions. Car plants and workshops responded with strikes and thousands of workers joined the miners on the picket line, forcing the police to close the depot. Scargill described it as the “greatest day of my life” as “the picket line didn’t close Saltley, what happened was the working class closed Saltley” demonstrating its power (p.76).

He wasn’t the only one who recognised the importance of these events. In her autobiography, Thatcher says: “For me, what happened at Saltley took on no less significance than it did for the Left”(59). She explained:

In February 1972 mass pickets led by Arthur Scargill forced the closure of the Saltley Coke Depot in Birmingham by sheer weight of numbers…it was a frightening demonstration of the impotence of the police…and it lent substance to the myth that the NUM had the power to make or break British governments, or at the very least the power to veto any policy threatening their interests by preventing coal getting to power stations(60).

Nevertheless, the miners won what the authors describe as their “greatest victory” (p.77). However, the underlying problems in the industry were unresolved and the question marks over its future and the government’s reluctance to further increase wages led to another strike ballot within two years. It produced an overwhelming majority for action with 93% in favour in South Wales and 86% in Durham. The strike was set for 9 February 1974. Tory Prime minister Heath called a general election in response, on the basis of “Who governs?”. He was told ‘not you’ by the electorate and Labour returned to office and settled the strike ten days later (p.78).

The new Labour government agreed a Plan for Coal with the NUM, providing for the development of the industry with increased output, investment in new technology and new super-pits. The aim was for a move back to coal from oil and to develop coal-based petrochemicals. But Labour was a government of crisis in a period of global capitalist crisis. Labour came to power as a long-term decline in profitability was exacerbated by the OPEC oil price rises, stoking a growing scepticism among an influential section of the ruling class about the continued effectiveness of Keynesianism as a method of managing capitalism. Committed to a “fundamental and irreversible shift in the balance of power in favour of working people and their families”, instead Labour’s leaders buckled to international and domestic pressure to attempt to rescue British capitalism at the expense of working people. In 1976, despite efforts by Tony Benn in Cabinet to push an Alternative Economic Strategy, James Callaghan’s government agreed to the terms of an IMF loan and just two years after being signed the Plan for Coal was “dangerously weakened” (p.82).

For miners, this meant a divisive incentive scheme which set area against area, a decline in coal production, further pit closures and increased pressure from the introduction of highly mechanised faces and wage restraint (p. 79). For all workers, it meant the slashing of public spending and wage cuts demanded by the IMF to meet the conditions of the bail out. Unsurprisingly workers kicked back, which led to widespread strike action culminating in the so-called Winter of Discontent.

1984-85

After the failings of Labour, the Tories under Thatcher won a resounding victory in 1979 and set about making Britain a land safe for shareholders. Their first target was the trade unions. The Tories had prepared in advance with the “Stepping Stones” report from Thatcher’s adviser John Hoskyns and Norman Strauss from Lever Brothers and the action plan drawn up by Nicholas Ridley (both in 1977). The “Stepping Stones” report identified ‘the negative role of the trades unions’ as one of the major obstacles to “national recovery”. The “Ridley Report” was leaked to the Economist in May 1978 setting out detailed plans for the next Tory government on how to approach the nationalised industries. A special annex on “Countering the political threat” was essentially a strategic manual for confronting and defeating the unions, chief among them being the miners.

The Tories had good reason to fear the miners as they were part of a general radicalisation in the labour movement, with formerly right wing Areas like Durham joining established left wing Areas like South Wales, leading to the election of Arthur Scargill as NUM president in 1981 with over 70% of the vote. But the Tories prepared the ground for the confrontation with the miners, picking off weaker unions first, bringing in anti-union legislation, changing the management within the NCB – above all bringing in the union buster Ian MacGregor. In an echo of Red Friday in 1925, the government retreated in 1981 when they weren’t yet ready. But by the spring of 1984 with coal stocks high, the police primed, the media on their side, private truck companies on standby, they were ready and so provoked the strike in March with the announcement of the closure of the viable pit at Cortonwood in Yorkshire. In response, a national strike spread area by area without a national ballot, which became both a focus of division and an excuse for the majority of Notts miners to work through the dispute.

Hundreds of books, articles, and papers have been written about the 1984-85 strike (many by these two authors) but the scale of the attack by the state on the mineworkers, their communities and their union is well captured by the simple accounting of the conflict:

20,000 miners were arrested or hospitalised. Two were charged with murder. Over 200 served time in custody, including the president of the Kent miners, who spent two weeks in jail. A total of 995 miners were victimised and sacked. Two miners were killed on picket lines, two died on their way there and in Yorkshire three teenage children died foraging for coal (pp.97-98).

These were the casualties of the class war unleashed by the British state against the miners and their families. Riot police occupied pit villages, police roadblocks prevented free movement across the country to anyone suspected of being an NUM picket, state violence and intimidation towards miners became commonplace culminating in the police riot at Orgreave, social security payments were cut for striking miners’ families, the union’s resources were seized by the state, and the state also intervened to quickly settle other disputes that might have joined forces with the miners to create a wider front against the government. The alleged thuggery of picketing miners was a constant news item at the time, but what was known by many then and is undeniable now is that the violence was primarily directed against miners (often just in T-shirts, jeans and trainers) by heavily armoured riot police with batons and shields, dogs and horses. What is astonishing is not any violence of the miners but their restraint – particularly considering they are a group of workers with familiarity with explosives.

Even with all this against them, and despite the failure of the TUC (under the latterday Jimmy Thomas, Norman Willis) to organise effective national strike action in support, or the Labour party leadership (under Kinnock, an MP from a mining constituency) to mobilise, there were moments during the dispute when it looked as though the miners could win. The solidarity of the majority of miners, the support of their communities, the active involvement of a substantial minority of women in the coalfield areas in running the support networks and, in so doing, upending traditional ideas of men’s and women’s roles in mining communities, were all positive developments during this unique moment in labour movement history. Massey and Wainwright describe how an overwhelmingly male, manual workforce, predominantly white, socially conservative, living in communities with traditional sexual divisions of labour, became the centre of “as broad a social and geographical base as any post-war radical political movement.”(61) The support came from expected sources like the trade union movement and left political groups, but also the wider urban working class (both black and white) in the cities, the women’s movement, LGBT groups, the black and Asian community more generally including in its organised religious form (with support from faith groups in mosques and Sikh and Hindu temples), the peace movement and environmentalists. It transformed both sides. New alliances and new ways of working together meant that the strike showed the possibility of “a different direction for class politics”(62). In some respects what was done was a new departure for the NUM as in the link between the Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners group and Welsh miners dramatised in the film Pride. But also some of what was done was not so much new as the revival of old alliances and rejuvenating older traditions. For example, the South Wales miners had a long tradition of internationalism, anti-racism, anti-fascism and solidarity: chasing Mosley’s Blackshirts out of Tonypandy in 1936; the many members who volunteered to fight in the Spanish Civil War(63); the long relationship with, and the championing of, Paul Robeson against McCarthyite attacks; the coachloads of miners sent by the South Wales NUM to join the mass picket in support of the mostly Asian women workers at Grunwick in 1977-78; and the strike action taken in support of nurses in 1982. Creating a ‘culture of solidarity’ before the 1984-85 strike built longer term relationships in some cases of mutual support. For example, one Brent activist commented during the 1984-85 strike that “we had people, the Indian community in particular, saying they were supporting the miners because of the support they gave at Grunwick.”(64)

Nevertheless, the defeat was a bitter end to the strike, the miners having fought so hard for so long and having created a national and international network of support in money, food and support groups that was described by the Financial Times as “the biggest and most continuous civilian mobilisation to confront the government since the Second World War.”(65) Beynon and Hudson highlight what is often forgotten as:

The most profound fact of all: that 200,000 workers and their families could embark on what most of them considered to be a just strike and stay together for up to a year, with little or no official financial support, under the permanent bombardment of the media, the coal employer and the Thatcher government (p.129).

After the Strike

What the miners faced after the return to work was the rapid closure of pit after pit and a programme of punishment for what MacGregor termed their “insubordination”. For those who remained at work, the union was sidelined, management became more aggressive, redundancy payments were used to attempt to buy off any further opposition. A last gasp of opposition took place in 1992 with a one-day strike and two huge national demonstrations but the closures went ahead, although the government had to increase the levels of redundancy money. The next year, the 16 mines left (of the 219 operating in 1980) were privatised and in 1995, Tower, one of the South Wales pits due for closure was bought by the miners themselves with their redundancy pay. It then provided work for hundreds of miners until the reserves were finally exhausted and it closed in 2008.

With all the pits in South Wales and Durham closed (apart from the Tower cooperative), both regions looked to central government for help in replacing the thousands of relatively well-paid jobs lost with the end of deep mining. All sorts of government schemes and organisations were given the task of assisting in ‘regeneration’ and after the landslide victory of Labour in 1997, there was hope that things would change for the better with large scale government intervention.

The coal mining communities in South Wales were often isolated by the geography of the valleys in which they are located. It was (and to a large extent remains) easier to follow the valley down to the coastal plain cities of Cardiff, Swansea and Newport than it is to cross from one valley to the neighbouring valley. In a pattern commonly seen in Britain’s colonies(66), here an enduring effect of that imperial character of Welsh industrial society in the late 19th century, the railway lines head from the valleys to the ports and the steelworks on the coast, betraying their origin as primarily networks for the carriage of coal rather than the carriage of people. The Durham coalfield was different in that it was divided between the older pit villages in the west of the county and the newer workings on the eastern coast. But in both coalfields, with the decline and eventual end of deep mining, the very reason for these settlements ceased to exist and they were left to deal with the long term health impacts of mining on coalfield communities – another factor that was not properly recognised by government.

In Capital, Marx talks about capital coming into the world “dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt.”(67) Nowhere is that truer than in the mining industry, which was a dangerous occupation from the start of its history in Britain (even today miners are killed and injured in the tiny number of small privately owned mines remaining). The big mining disasters capture the attention of the media – such as the 1913 Senghenydd disaster which killed 439 miners and a rescuer or the 1934 Gresford explosion which claimed the lives of 265 and the very different disaster of Aberfan. But danger was ever present in the day-to-day work in the pits with smaller scale incidents regularly leading to injuries or fatalities.

Looking back on his nine years working underground, Bevan never forgot the routine and daily possibility of serious injury or death: “runaway trams hurtling down the lines; frightened ponies kicking and mauling in the dark, explosions, fire, drowning.”(68) And there were the long-term disabilities contracted by so many miners ranging from vibration white finger to a variety of lung conditions. In the 1970s, for every miner killed in an accident in the pit, seven contracted pneumoconiosis (‘the dust’) and every day a miner died from it. Mid Glamorgan, West Glamorgan and Gwent in South Wales consistently recorded the highest rates of long-term illness in Britain, closely followed by Easington in the Durham coalfield (p.265).

Essentially the view of the Labour governments of Blair and Brown was much the same as the Conservative government that they replaced, in that – with a modicum of government help – the market will provide. Of course, it didn’t – or at least it didn’t provide anywhere near enough decent, secure jobs at a living wage. What it did provide was a lot of low paid, insecure service jobs in the private sector and then the government provided some public sector jobs – particularly in health and education, many of which employed women. Not all of the public sector jobs were particularly well paid, and many quickly became vulnerable to privatisation and contracting out. The impact on the coalfields was catastrophic with mass unemployment and increases in crime, drug use and a loss of community (p.239); shops and amenities closed, and a growth in empty rundown housing stock as people left the area in search of work.

With the return of the Tories after the New Labour interlude, the full force of the austerity programme hit the coalfields, disproportionately impacting the areas of the country that were already suffering from deindustrialisation. In the case of South Wales, this is partly because it is disproportionately reliant on public sector employment. A deliberate regional policy of the Labour governments of the 1960s and 1970s was the “dispersal” of civil service jobs to Wales (and other deindustrialising parts of the UK) from the south east of England). Large employers like DVLA in Swansea, ONS in Newport and Companies House in Cardiff (with many commuting from former coal mining communities) were seen as replacements for the loss of jobs in coal and heavy industry. As a result, Wales has a higher ratio of civil servants per member of population than London at 105 in every 10,000. With 20% of the Welsh workforce employed in the public sector, it is more than three points higher than the UK average (it was over 27% just before the 2008 crisis). Cuts to the public sector therefore hit both in terms of job losses themselves and because public sector jobs tended to be the better paid jobs in the community.

The employment figures for the former coalfields were massaged by a concerted effort to persuade ex-miners to register as sick rather than unemployed. The fact that thousands of ex-miners did suffer from mining-related illness and that there was not enough work available anyway came way behind the government’s desire to show that the coalfields were recovering and that unemployment was decreasing. By 2004, the figure for working age men in South Wales in receipt of invalidity benefit was 19% and in Durham it was 16% (p.262). To rub salt into the wounds, the government was pocketing half the surplus generated by the miners’ pension scheme and critics claimed this effectively meant that the miners were paying for their own invalidity benefit.

The authors point out that the NUM’s role in fighting for miners’ health, and compensation for those injured or disabled, continued (and continues today) long after the last deep mine was closed and ensures the lasting relevance of the miners’ union to coalfield communities. Over the years of nationalisation, the authors argue that the union too often pulled its punches, even to the extent of collusion with the Board over the long term health risks to miners, and settled cases before they went to court, saving the Board money and saving face for the NUM (p.278). But as coalmining wound down and was followed by privatisation, the union no longer felt any commitment to a nationalised industry and so launched a series of court cases in South Wales and Durham which were very successful and gained millions of pounds in compensation for disabled miners.

Beynon and Hudson point to the physical challenge and the dangers of mineworking as helping to explain the political nature of mining trade unionism (p.10). Underground work had low levels of supervision but high levels of co-operation and reliance on workmates. In Durham, the work was organised so that hewers (cutting the coal) worked in pairs of ‘marras’ (mates) (p.11). In South Wales work was arranged differently but there was an equally vital reliance on work mates (‘butties’). Both experiences of the labour process, and its mode of political translation, have some parallels with that of the Bolivian miners described by García Linera in which the:

Productive and specifically technical self-esteem of labour in the labour-process gave rise, over time, to the centrality of class, which would appear to be the means by which the mineworker’s productive and objective position in the mine transferred to the realm of the state and politics.

The location of pit villages and the dominance of the mine as the prime employer within many coalfield communities gave miners and hence their union, and specifically the lodge, a pre-eminent place in local civic society. Unlike the industrial developments of Lancashire and Yorkshire and the Midlands, industrialisation in the coalfields did not go hand in hand with the creation of a large local capitalist class or a supporting middle class of professionals and small businesses. The population was overwhelmingly working class with the tiny minority of coal owners and iron masters sitting above a narrow layer of professionals and small shopkeepers.

Within those communities, with the lodge at the centre, the miners built an entire counter-culture like no other British trade union. With the networks of miners’ institutes and libraries they created educational, sporting, artistic and musical (including choirs and bands) opportunities for the local community(69). They also built health and welfare services before the creation of the welfare state — Bevan as Health Minister in 1945 drew heavily on the model of the Tredegar Medical Aid Society with which he grew up). The authors point to these institutions as “clear markers of a powerful working-class culture [and] are perhaps the most significant features of mining trade unionism” (p.18).

As well as their industrial organisation at the workplace and their social impact in the community, the miners’ unions had early on looked for political representation – first from the Liberals, then at the turn of the twentieth century, from the newly formed Labour party. The social weight of the miners in their communities meant that with universal suffrage the miners, their union and their eventual chosen political vehicle – the Labour party – dominated the political landscape of the coalfield. Beynon and Hudson point out that in the 1929 general election (the first after the General Strike) when Labour won the most seats for the first time, every constituency in the Durham and South Wales coalfields returned a Labour MP (p. 25). The 1931 election in which former Labour leader McDonald joined the Conservatives to form a National Government was catastrophic for Labour with a net loss of 241 seats. Yet even then, the Labour vote increased in South Wales with Labour recording a 20% increase over 1929 in Rhondda West in the heart of the coalfield and four South Wales seats returning Labour MPs unopposed (p.26). The contrast with Durham (where Labour’s MPs reduced from 10 to 2 and the vote went down by 10%) is explained by the deep roots of the radical politics embraced in the South Wales valleys under the impact of the campaigning work of the Fed in the 1920s.

On a representative level the South Wales and Durham influence on Labour was enormous, producing seven Labour leaders elected from constituencies in these two regions, and the architects of the welfare state in Nye Bevan and Jim Griffiths. But this embrace of radical politics had limits. One of the questions left unanswered by the authors is why was it that, despite the overt socialism of the Fed in South Wales, the impact on the political direction of Labour in the coalfield and Wales more widely was so limited? Did the influence of the radical syndicalism of the advocates of the Miners’ Next Step inadvertently assist the Labour Right’s insistence on imposing a division of labour between the ‘industrial and political wings’ of the movement? Bevan stands out as a left-wing miners’ MP partly because there were so few left-wing miners that made it to Parliament (S. O. Davies was another). As Campbell says “taken as a whole, with notable exceptions, the miners’ MPs have been the solid ballast of the Parliamentary Labour Party, not its stars or leaders; they have been marked by moderation, loyalty and a certain dullness.”(70) That’s not to say that the NUM did not engage with the Labour party. It did. It was an important affiliate and sent its delegates to conferences and lobbied ministers and shadow ministers to pursue its policy.

Political Transmission – beyond nowhere else to go

In the 1960s the scale of pit closures “removed the miners and their union from their positions of dominance within the labour force and in civil society” (p.65). There were political implications to these changes in the social structure and party loyalties became strained. In their respective regional labour movements, the NUM increasingly lost its position of leadership to the TGWU in South Wales and the GMWU in Durham. But even then, the union retained huge respect and influence – particularly in the South Wales labour movement. Yet there does not appear to be much evidence of it systematically attempting to mobilise its membership or wider networks of support to take an active part in the local Labour parties to push Labour at council level or Welsh Labour MPs significantly to the left.

South Wales was effectively a one-party state for most of the post war period, with total Labour dominance over local authorities and most of the parliamentary representation in the coalfield. But it was not a bastion of radical socialist politics. For example, it is notable that Welsh Labour councils were completely absent from the municipal battles of Labour councils like Clay Cross in the 1970s or the GLC, Liverpool, Lambeth and others in the 1980s.

Labour councils in South Wales remained strongholds of the traditional right-wing of the party as did the Welsh Parliamentary Labour Party. In the period of post war economic boom, they built much needed council houses and improved local facilities, in the wake of the capitalist crises after 1973 and in 2008 they were lost. They were often unimaginative in their approach to the local economy and local life, unresponsive to local opinion, uninterested in the extension of local democracy and became complacent in their town hall offices. Since the 1980s the best that could be said of them was that they tried to apply the theory of the ‘dented shield’ – that is, rather than fight the cuts, ameliorate the worst of them. All of this contributed to what the authors describe as “a lost community and an atrophied local Party peopled largely by elderly men” (p.333). The authors quote Peter Hain’s 2019 observation: “I’ve noticed how the whole base of the Labour party has dissolved under our feet, as it were, in old strongholds like Neath and right across the South Wales valleys” (p.333). The picture was similar in Durham.

For those prepared to look beyond the complacent expectation that these areas would remain safe seats for Labour forever, there were warning signs of a problem in both Durham and South Wales. The Labour vote was generally in long-term decline with sporadic exceptions (such as in 1997 after 18 years of Tory rule and in Corbyn’s first general election as leader in 2017). But this decline was probably ignored because it was from a spectacularly high starting point – for example, in 1966 Labour received 81% of the vote in Easington, 74% in North West Durham and 71% in the City of Durham. In South Wales in 1966, Labour won 78% in Aberavon, 77% in Caerphilly, 76% in Llanelli, 79% in Neath, 78% in Ogmore and 75% in Pontypridd. Although many of the constituencies still showed high Labour votes in 2015, there were the beginnings of cracks appearing – for instance the vote in North West Durham and the City of Durham went down in both places to 47%.

The Brexit vote was like an explosion under the feet of the mainstream political elites in 2016 and little has remained the same since with the authors pointing out that

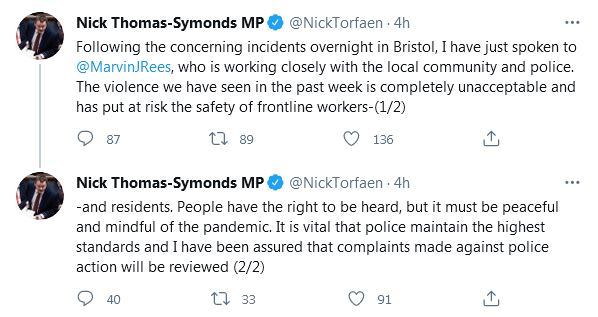

While the core support for leaving had been in the south and east, it was the working-class vote in the north of England and in South Wales that tipped the balance. In the old coalfield areas, the result was a landslide. Six of the ten constituencies in Durham recorded Leave votes of over 60 per cent, as did Blaenau Gwent and Torfaen, with smaller majorities elsewhere (pp.320-321).

Beynon and Hudson argue that this was not as a result of ignorance, lack of education or xenophobia as much of the liberal commentariat seemed to think. Rather it was the result of many things, not least a feeling of being taken for granted for too long. It may be that the palpable sense of decline in communities which had lost their purpose to exist fuelled a disillusionment with all levels of government and a relative depoliticisation which took advantage of a rare opportunity to kick back in some way, to demonstrate that people cannot be ignored. In the authors’ words, the Brexit vote was a “forgotten people striking back” (p.1). That the vehicle for this was led by the populist Right coloured the understanding of the vote. The Brexit vote was:

More like a reaction to the series of injuries – the sequential acts of material and symbolic violence – that had been inflicted on these people and their households over the previous thirty years. Seen from this perspective, there was a strong class element to the referendum (p.322).

They argue that

Forms of nationalism and right-wing populism were on the rise, aggravated by deep feelings of resignation and a sense of hopelessness and sometimes anger that all the jobs had gone and places been forgotten, with many promises broken (p.322).

They point to earlier “straws in the wind” such as Gordon Brown’s shameful attempt to take advantage of anti-migrant feeling with his “British jobs for British workers” speech. They explain that there was growing worker discontent over how EU freedom of movement was being interpreted, specifically “companies that obtained contracts in the UK able to post their own workers to the jobs” (p.321). But this isn’t the whole story. The anger that certainly did exist over the Posted Workers Directive on large construction sites was because foreign companies were winning contracts and bringing their own workers to the jobs, but crucially were not bound by national agreements. They were only obligated to abide by the host country law in relation to employment practices so, for example, they had to pay the statutory minimum wage but were not obliged to pay the rates and conditions stipulated in the national agreement between the UK employers and unions (this is not set out in the book). This was the key element of workers’ and union objections because these actions were designed to undercut national agreements so that contract companies with workers from Italy and Portugal, as in the Lindsey Oil Refinery case cited, could be employed at rates below those negotiated by the UK unions with the British employers.

As then TUC general secretary Brendan Barber commented:

The EU’s Posted Workers Directive has been implemented in the UK in a way that fails to guarantee UK agreements, and recent EU court judgements have raised even more worries that the law favours employers that try to undermine existing standards(71).

It is certainly true that the fascist BNP quickly latched on to this with placards produced, demanding ‘British Jobs for British Workers’. Although there were definitely xenophobic views among some of the strikers, these were contested by the stewards and there was a lively discussion among the strikers about the use of that slogan, many feeling that it misrepresented the core of the dispute, especially as many of the workers themselves had worked abroad and there were locally resident Polish workers among the strikers too. The stewards quickly ensured that the handful of fascists who had tried to make capital out of the dispute were physically removed(72). While the authors are right that the Remain campaign never clearly addressed workers’ concerns, the Lindsey dispute shows that although xenophobia can be “a real problem for the trade union leadership” (p.321) if local stewards confront these views and articulate an alternative position based on shared working class interests, it is possible to win the argument – or at least isolate and nullify the racist minority. Interestingly, research on why people voted for Brexit in the South Wales valleys suggests that while immigration was a key factor, the overwhelming motivation behind this was not racism or xenophobia (or at least racism or xenophobia directly) but concerns about jobs, pay and public services.